Pontefract is a 2012 Twine Gothic horror game by Kitty Horrorshow. In this blog post I will talk about the game generally, but specifically my aim is to tentatively theorize how Horrorshow’s game makes use of Shakespearean allusion, what affordances its buys her as a creator, with the overall goal of opening up questions of what this might mean for us (me and my cohort) as Shakespearean and early modern scholars.

In Pontefract, the player takes on the role of an unnamed character, perhaps a knight, in a Gothic fantasyscape. You work your way through several rooms of a semi-abandoned castle, populated only by apparently undead humans. Primarily how the games works is this: you enter a room. The room is described, sometimes with occasional observable details (for instance, when entering the kitchen, instead of directly confronting the cook you can check out what she’s boiling in her cauldrons). If there is an NPC in this room, they will ignore you, instead carrying out routines (praying, cooking, being eaten by a floating horse’s head) that bespeak either their undead qualities (ie, they are zombies, not fully human, and only carry out certain deeply wired routines) or their artificiality (they are, in the most literal sense, videogame NPCs, written only to carry out certain limited, repetitive behaviors).

You can choose to interact with these characters, at which point you are presented with two options. The first is always “friendly” — you either attempt to get the NPC’s attention, or help them if they seem to be in trouble. The second is always hostile, and involves drawing your sword to kill the NPC. For three NPCs you meet — a priest, a stablehand, and a cook — choosing the friendly option will result in your character’s death.

Progression in the game involves killing these NPCs. After being slain they leave you with keys which will unlock the door to the castle dungeon. You know you want to do this — apart from the fact that a locked door in a videogame always implies the goal is to open it — due to an encounter with the fourth NPC in this section of the game, the so-called “Pale King,” who sits eyeless and presumably also undead in the castle’s throne room.

This is the only NPC with whom you have no options for interaction. Instead, when meeting him he speaks “into your thoughts [with] a hundred clamorous voices”:

HAVE I NO FRIEND WILL RID ME OF THIS LIVING FEAR? I WOULD THOU WERT THE MAN THAT WOULD DIVORCE THIS TERROR FROM MY HEART.

Somehow, you understand that the ‘terror’ of which the pale king speaks is locked away within the castle dungeon.

You take knee before the king and vow to rid him of that which grieves him so, before standing and turning to descend the stairs back to the great hall.

The line spoken by the Pale King is from Shakespeare’s Richard II, very close to the end of the play, and is curious enough in and of itself. Henry Bolingbroke has recently deposed and imprisoned the rightful king, Richard II, and named himself Henry IV; in Act V, scene 3, Henry uncovers a plot against him by some nobles loyal to Richard and has most of the conspirators put to death. In the next scene (V.4), a nobleman named Exton enters with his servant. The scene is brief, so I will reproduce it here in full for you to see just how odd it is:

Exton

Didst thou not mark the king, what words he spake,

‘Have I no friend will rid me of this living fear?’

Was it not so?

Servant

These were his very words.

Exton

‘Have I no friend?’ quoth he: he spake it twice,

And urged it twice together, did he not?

Servant

He did.

Exton

And speaking it, he wistly look’d on me,

And who should say, ‘I would thou wert the man’

That would divorce this terror from my heart;’

Meaning the king at Pomfret. Come, let’s go:

I am the king’s friend, and will rid his foe.

Exeunt

So Horrorshow’s Pale King quotes Henry IV, but only as he himself is quoted by Exton. The scene to which Exton refers, in which the king speaks these lines, is not one we ourselves are allowed to see: the previous scene where Henry uncovers the plot against him contains nothing close to the statements that Exton attributes to him. In fact, going thoroughly from the text, Exton hasn’t even shown up prior to this point in the play.

This scene seems to pointedly highlight the lengths to which the ambitious Exton is willfully misinterpreting the situation, if not in what Henry is referring to, at least in the fact that Henry is personally addressing the order to him: “And speaking it, he wistly look’d on me, / And who should say, ‘I would thou wert the man'[.]” (Compare Horrorshow’s: “Somehow, you understand that the ‘terror’ of which the pale king speaks is locked away within the castle dungeon.”)

Indeed, the play ends with Exton presenting Henry with Richard’s corpse and Henry, horrified at what has been carried out in his name, disavows himself of Exton and the act committed for his benefit (though, of course, he does benefit).

In Horrorshow’s game the command is given directly and unambiguously, placing us in the shoes of a character who is and is not Exton. It should come as no surprise to a player familiar with Shakespeare that when you venture down into the dungeon what you find is a weakened, miserable figure “you” immediately recognize as the “rightful king.”

Again you are presented with a choice: to peacefully beg forgiveness from the rightful king, or to kill him. As before, the peaceful option proves ineffectual, but this time, not because it kills you. Rather:

You attempt to kneel before the rightful king, ready to apologize for your wrongful deeds and vow yourself to his cause, but your body resists you. The castle shudders and the walls begin to wail, and your head is filled with the lurching, ragged language of the stones.

NO. KILL HIM.

At this point you again have the same choice, and the only way to move forward is to kill the king. The game ends immediately after: you die as the castle collapses around you, but almost immediately you find yourself once again in the woods outside the castle gates, preparing to enter. The implication, perhaps, is that you are no different than the creatures that trace their endless, undying routines within the castle walls: as a player, you are finally robbed of the agency the game has dangled in front of you at every turn with its false choices, and you are at last subsumed into the machinery of the Gothic landscape.

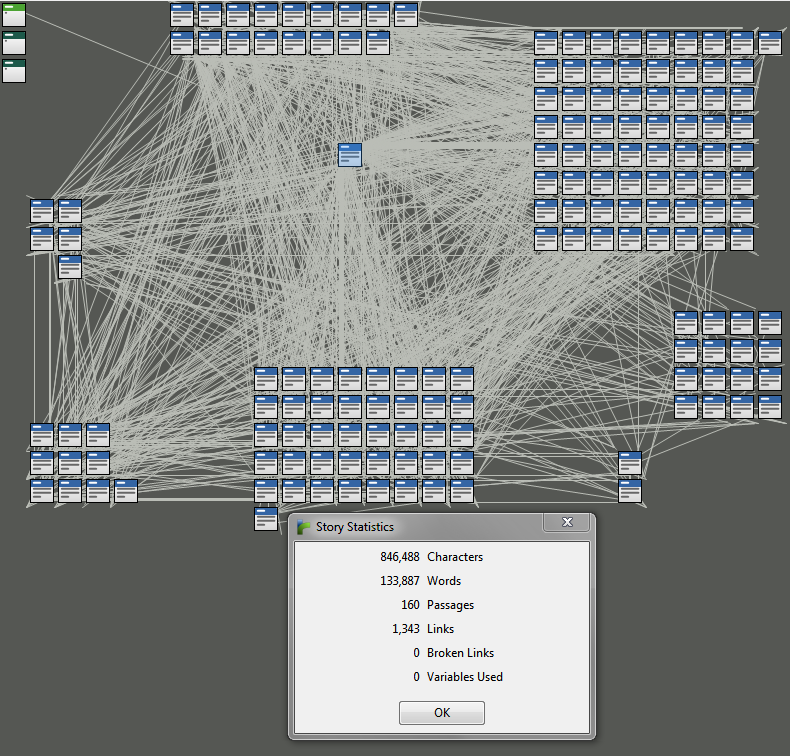

Appropriately enough, Horrorshow’s hypertext game seems to adapt and extend Gérard Genette’s pre-Internet idea of hypertextuality as “any relationship uniting a text B (which I shall call the hypertext) to an earlier text A (I shall, of course, call it the hypotext), upon which it is grafted in a manner that is not that of commentary” (Palimpsest: Literature in the Second Degree 5). Rather than a simple allusiveness, or even a dense and methodical rewriting (eg, as between Homer’s Odyssey and Joyce’s Ulysses), Horrorshow’s references to Shakespeare are more like the hypertextual apparatus of Twine itself: links that send us outside the text, or into another text, or a different part of the same text, but which do not do so to make a claim about Shakespeare or Richard II. Rather, both texts become hypertexts, existing in tandem or parallel, creating a space for thematic echos and reader (re)orientation.

Exton makes a choice; we do not. Exton must interpret what he will do; we must interpret what we have done, if we have done anything. It is Exton who allows the play its end, and despite his abjection, the consequences of his actions haunt the rest of Henry IV’s reign. Our actions have, perhaps, no lasting effect in the larger context of the game’s endlessly looping plot, as we are simultaneously trapped within and enabled by the haunted house that is the game’s architecture. Apart from Shakespeare, then, I would say Horrorshow’s game is commenting on the heroic power fantasy of videogames and the exhausted narratives of aggressive but ultimately impotent of bloodshed they often foster.

As a matter of fact, Horrorshow’s original post about the game makes no mention of Shakespeare at all, and so it’s possible many who played through it did not note the allusions if they had no foreknowledge. The game is deeply allusive, but the allusions only “activate” for a player quite attuned to Shakespeare’s play — and nevertheless, the allusiveness is not present in any way that would seem to lessen the enjoyment of a player who didn’t know Shakespeare but who was very familiar with the Diablo game franchise, text adventures, or someone who wanted to poke around a haunted castle.

Overall, the game draws deeply from Shakespeare while also meticulously managing the impact of its Shakespearean connections through a variety of tactics, including letting its allusiveness go unspoken, choosing its allusions obscurely, or interweaving its allusions with formal misdirection. Indeed, the “living fear” Exton says Henry decries is interpreted as the deposed king imprisoned at Pomfret — Shakespeare’s name for Pontefract, the actual castle where the historical Richard II was held captive until his execution. Thus the games title is itself an allusion that displaces Shakespeare as a central, authoritative voice of historical record, underscoring the gap in terminology between our understanding of history and his.

Furthermore, Richard II is not a play that looms large in the popular consciousness, or at least, not large enough for Shakespearean capital to immediately pay off in a gaming environment as it does, say, when the text at hand is Hamlet or Hamlet or Hamlet or Hamlet or Hamlet. Indeed, the lines from Richard II in Pontefract are not the most memorable of Shakespeare’s lines; they’re not even the most famous lines from Richard II. Nevertheless, Horrorshow puts her obscure citations to work.

After beheading the rightful king, the castle appears to collapse and you hear the severed head whisper to you the game’s second direct lift from Shakespeare: “Grief boundeth where it falls.” This is not, as it happens, anything spoken by Richard, but rather a comment made by the Duchess of Gloucester near the very beginning of the play (I.2) when she is urging John of Gaunt to stand up for her husband (whose death she believes Richard sponsored), and implicitly foretelling the whiplash of political instability that will come to shadow the reign of Henry IV.

In Pontefract the player is primed for this line differently, as you descend to the dungeon and the game tells you,

The castle whispers to you.

Dost thou at ev’ry hail draw out thy sword?

From whither comes this eagerness to slay?

Thy lust for blood and anguish sees thee curs’t

These three lines of blank verse generically meld with the Shakespearean quotations, though they are not themselves Shakespeare (as far as I can tell, they are original). Thus, any player not explicitly looking for Shakespearean allusions might be inclined to read the actual quotations from Shakespeare — if they seemed somehow stylistically distinct from the game’s narrative voice — as of a piece with this verse. The final word in the quote above is a hyperlink, which takes us to a closing line:

ttO suffERRr EverR thISSs accuRRSSedd dDAyy

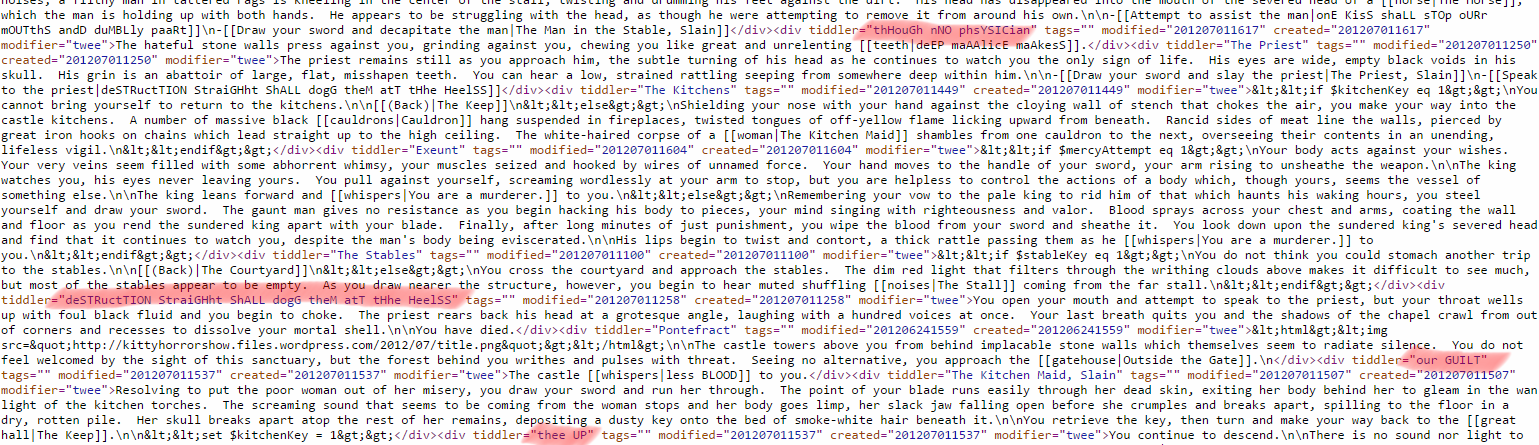

The styling of the text here — breaking with typographical convention to suggest the words are being spoken/thought in a hiss, or by an inhuman voice — recurs not only in her original post about the game (“P0ntteEFFraccctTTt”) but in the game’s code, where Horrorshow has named several passages after direct quotes from Shakespeare’s play in the same style:

It was not until the game was re-collated in a directory page that the author’s note made the Shakespeare connection clear, “inspired by” Richard II, which provides the reader with an introductory signpost for the allusions. I don’t meant to imply that Horrorshow is somehow “coming clean” about her allusions, but rather, the broad and subtle nature of the game’s allusiveness indicates a way of approaching Shakespeare that makes productive use of his corpus while insisting it is not the only corpus that matters.

Horrorshow’s Shakespeare is not an impeachable paragon of literature and humanity; he is the writer of Richard II as well as Hamlet, and also the author of dozens of less than memorable lines, dozens of less than memorable images. Neither is Horrorshow’s Shakespeare an academic Shakespeare, a layered site where the machinations of cultural poetics are put on display if we perform an anatomy with right critical tool.

However, there is indeed something here of the Foucauldian author-function. As Marjorie Garber has argued regarding the great dearth of personal and biographical information we have on Shakespeare, it is possibly exactly this dearth that makes Shakespeare such a literary powerhouse: “Freed from the trammels of a knowable ‘authorial intention,’ the author paradoxically gains power rather than losing it, assuming a different kind of kind of authority that renders him in effect his own ghost” (Shakespeare’s Ghost Writers 15).

Garber argues it is precisely Shakespeare’s ghostly nature that allows him to “possess” writers as distinct as Marx, Freud, and Derrida, whose use of his texts as examples for their theories means those theories forever thereafter exhibit the marks of a Shakespearean ghost-writing process. But I do not think we can say the same about Horrorshow’s game: her allusiveness is never to Shakespeare-as-such, not like, for instance, the way Freud “uses” Hamlet to explain his thesis of repression.

I would like to suggest, then, that Horrorshow and Shakespeare work collaboratively. What I mean is Shakespeare becomes not so much an author-function but an author-medium. By “medium” here I mean something akin to what Marshall McLuhan means when she says “All media are active metaphors in their power to translate experience in new forms” (Understanding Media 85). This is similar to the way in which Garber argues Shakespeare ghost-writes Freud, Marx, and Derrida — there are things these writers wish to articulate, and Shakespeare provides the vocabulary for doing so.

But it is always Shakespeare’s vocabulary. The authors work to preserve a whole and bounded idea of “Shakespeare” outside their own texts. Horrorshow’s Shakespeare, however, becomes an active but epehemeral metaphor for the experience of authorship and creation. Is Shakespeare ghost-writing Pontefract, or is Horrorshow ghost-writing Shakespeare?

Her textual use of Shakespeare blurs the boundaries between her in 2012 and him in 1595. His blank verse appears alongside hers; shreds and patches of his words appear in the very underlying structure of of the game, rewritten in Horrorshow’s own typographical idiolect, meaning nothing in situ, hidden from the player, but serving as the connective tissue between the blocks of the story.

In the end, the game is not “based on” Richard II or an adaptation, but “inspired by.” Horrorshow makes use of Shakespeare as one part of an available arsenal as a creator and — perhaps, disclosing now that my interpretation of Pontefract is as precarious as any one might offer — to express her interests and concerns regarding games and the stories of power and responsibility they can dramatize for us.