Before I get started on this, I need to explain a bit about how this piece of criticism came about, to establish my rhetorical situation.

About five years ago at Wal-mart, on a total whim, I purchased a multi-DVD set of 50 “classic” horror movies, wherein classic means “a few famous things in the public domain and a bunch of stuff that costs nothing or next to nothing to license.” There’s some good stuff in there – like the original Night of the Living Dead, Nosferatu, The Phantom of the Opera, and Carnival of Souls – but for the most part it’s filled with B-movie shlock like The Killer Shrews or Creature from the Haunted Sea. At the time my plan was to watch every single one of these movies in alphabetical order and write reviews for this blog, but the plan never came to fruition because it was conceived through boredom rather than any actual drive.

However, I decided one good possibility for my Patreon would be to return to these films and, using a random number picker, select two arbitrary movies and attempt to write a comparative analysis of them. That’s what happened this month, serving up the films The Vampire Bat (1933) and Bloodlust (1961). The films themselves are totally different in content; the former is a post-Dracula vampire picture while the latter is an awkward ripoff of “The Most Dangerous Game” and, I’d argue, a primitive slasher film ancestor. Unexpectedly, however, they both have in common a central concern: who gets to decide who dies?

Critical theorist Achille Mbembe considers the term necropolitics as a set of political moves, the “ultimate expression of sovereignty” that resides “in the power and the capacity to dictate who may live and who must die.” So, for example, the power of the state to order the execution of criminals, or from a critical animal studies perspective, the assumed right of humans to enact wholesale slaughter via factory farms, and things of this nature. Of particular interest for Mbembe is the explicitly authoritarian valence of necropolitics, the version of it that arises in societies ordered around “the generalized instrumentalization of human existence and the material destruction of human bodies and populations.” (Think here, of course, of Nazi Germany, but also the many colonial enterprises worldwide and their projects of enslavement and exploitation of certain populations.)

This is heady stuff, but for now we can consider the barest bones of Mbembe’s conception in order to think about what these two not necessarily very good horror films can tell us about the orientation of popular, white American necropolitics over the span of some thirty years. We’ll begin at the beginning, or at least in 1933, and The Vampire Bat.

Elevator pitch: a small German town is overcome with panic after a rash of mysterious murders in which victims were left exsanguinated with small puncture wounds on their necks. The city fathers insist that a vampiric curse has returned to plague the town, pointing to local history and folklore to prove it, while police inspector Karl Breettschneider believes there’s a more rational explanation.

The town’s suspicion turns toward a man with intellectual disabilities named Herman, who has no home but wanders the streets and survives on alms. When he overhears a local connecting the rising bat population in town with the vampire episodes, Herman insists that the bats are his “friends” and “soft like cats”. As the local then insists, re: Herman, he “prowls the streets all night, just like an animal” and “never works and never bathes, and yet appears well fed always.” While Herman himself is not played in a particularly savory light (unlike more recent ideas of Oscar-baity depictions of disability in film), he’s also clearly not harmful, as the objection he looks too healthy for a homeless person is patently absurd: he’s cared for by the community, and indeed, the first (witnessed) death in the film is of an old woman who fed him and employed him in minor jobs. Yet Herman’s proximity to this charitable dead woman only bolsters the town’s suspicions.

The Vampire Bat is doing something very interesting with vampire mythology here. Lugosi’s Dracula was only three years old at this point, fresh in the public memory, and the idea of suave, composed, and aristocratic vampires was really starting to gel in the popular consciousness. Of course, these ideas derived from Bram Stoker’s novel, which uses the figure of the Count to embody industrial Britain’s fears regarding a decaying but not entirely dead Continental aristocracy. However, if you dig back far enough into vampire folklore, you find that as the superstition emerges in the Balkans and Prussia it is particular to the peasant class of those regions. That is to say, our earliest recorded “vampires” in history were not aristocrats but peasants who supposedly had died but came back to life and looked unusually healthy. Signs of a possible vampire, indeed, were also generally signs of good health: shining eyes and a ruddy complexion (this is aside from appearing after a reported death and drinking blood, of course).

To reduce a complex historical phenomenon to a simple read for the purposes of argument, it’s easy to see how a myth that pathologizes healthy looking peasants benefits, more or less, the aristocratic power structure dependent upon those peasants by providing a mechanism for the laboring class to be suspicious and resentful of itself rather than its masters. What’s fascinating about The Vampire Bat, then, is that post-Dracula the filmmakers are revivifying an older version of vampire folklore, as the suspicions of Herman’s unusual good health indicate.

The finale of the film presents a final, bizarre turn of the screw, as a lynch mob descends on Herman, who jumps to his death from a precipice. It is assumed the vampire problem is solved, and yet – just after Herman’s death a final murder has occurred. The revelation of the final act is that Breettschneider’s acquaintance and the local doctor, Otto von Niemann, presented thus far as more or less an ally, is actually the murderer. Sort of. He’s also, inexplicably, a hypnotist, and he has been mind-controlling his servant to kidnap local people in the night, drag them to his laboratory, and then draining them of their blood – using the similarity to a vampire’s MO to divert suspicion from human agents.

But why does Von Niemann need all this blood? Because, as he explains, in his experiments he has “created life” and the organism he has somehow conjured is incomplete and not self-sustaining: it needs blood to survive. The specifics of this are glossed over and the whole turn of events is incredibly weird since, when it is revealed, the “life” Von Niemann has created appears to be a large immobile rock in an aquarium.

How this thing constitutes “life” in any sense of the term is certainly questionable. And yet, though I might be giving the film too much credit, I think that’s part of the point: Von Niemann justifies his actions by saying he must protect and sustain the new life he has created, and yet how is this thing, this horrible immobile clod, considered exceptional or sacrosanct “life” when compared with the human life of Herman, his caretakers, or the doctor’s other victims? The vampire, in the end, is metaphorical: Von Niemann’s Promethean technocratic delusions are parasitical upon the community he inhabits. His role as a doctor doubles his role as a necropolitician: he is there to heal the sick, but in fact grooms some of his patients for inevitable, instrumentalized slaughter for the sake of his weird barnacle child.

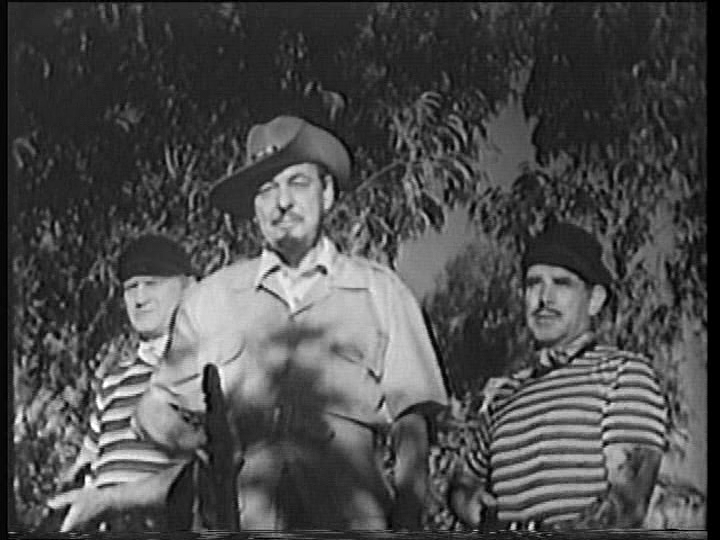

Bloodlust comes a number of years later, and yet there are some striking similarities to consider. As already mentioned, it’s a ripoff of the classic short story “The Most Dangerous Game” – a group of four “teenagers” (they all look considerably older) are on a boating trip and, because the captain of their rented boat gets blackout drunk, they decide to canoe to a nearby island, which they think is deserted. However, it turns out the island is host to Dr. Balleau, a wealthy eccentric, his wife, another drunk man they keep around for some reason, and a crew of servants/bodyguards in Venetian gondolier cosplay.

It turns out Dr. Balleau, whose home is decorated with stuffed and mounted game animals, has decided he needs to hunt something more challenging (humans, of course) and the two dudes of our group of hero teens are his next quarry. (Since his wife and the drunk dude are having an affair, he has them killed, and kindly informs our leading ladies he will merely keep them as sex slaves.) The teens (fine, we’ll call them that) are led into Balleau’s secret trophy room, where he has taxidermied his wife and her lover, as well as two other men (one of whom, I will note as an aside, is the only person of color to appear in either of these films).

Both of the hunts prior to his wife and her lover, Balleau explains, were inmates at a nearby island prison who were smuggled out by a certain boat captain – indeed, the teens’ captain, who has tried to sever ties but, it is suggested, grapples with what he’s done by drinking heavily. Anyway Balleau’s men somehow extract him from his boat and now he’s here, but he’s a huge asshole to the kids and won’t help them, instead striking out on his own (and getting killed).

As I mentioned before, one of the most “acceptable” sites of necropolitical action is the execution of prisoners by the state, and this is a function that Balleau has taken upon himself. As he tells our heroes, one of his previous hunts was a repeat rapist, and so deserved to die – the irony here, considering his plans for the two central women in the film, is apparently lost on him. He has installed himself as his island’s god and hence inhabits what theorists of necropolitics and biopower call sovereignty’s “state of exception” – he can, in short, dish out punishment, but under no circumstances is he subject to it. This gives the lie to his own description of the game, wherein he insists “my life will also be subject to how the hunt goes…” Indeed, Balleau’s occupation of the island, giving him ultimate control over a geographical space, enacts precisely the sort of colonial necropolitics Mbembe theorizes.

But there’s a backstory here. Balleau explains that he was once a “scholar” and indeed, he worked at a museum, preparing and designing exhibits. And then, he says, came “the war,” where he was enlisted as a sniper. He was disgusted to learn that he took “pleasure” in killing, and as he explains in one of the funniest, overdone lines of the film, the pleasure “became a passion, which became a lust – a lust for blood!” Bravo.

The second half of the movie involves a lot of running around and is, to be entirely frank, boring. At one point Balleau leaves his closest henchman for dead, and he loses track of the teens. However, they ambush him later that night, having hidden in his secret trophy room in the darkened exhibit he had reserved for their corpses. This is the point at which Balleau truly does becomes “subject to how the hunt goes,” revealing the uncanny side of the state of exception: being exempt from all punishment means you are also exempt from all protection. The henchman left for dead earlier now returns unexpectedly and murders Balleau, pressing him onto the mounting spikes of the teens’ would-be exhibit before dropping dead of his own wounds.

A quick read of this whole thing: there’s a suggestion here of Balleau carrying forward or embodying the horrifying trauma of World War II and its related atrocities, bringing these “teens” into confrontation with a mode of existence they, in their historical innocence, have been spared. Achille Mbembe’s theorization of necropolitics and necropower, taking as it does the modern context of globalized warfare, ends with his idea of “death-worlds, new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life conferring upon them the status of living dead” (think here of slavery in the US, or apartheid in its South African and Israeli forms, where whole populations are rendered pseudohuman in the eyes of state authority). Despite some anachronism, I would argue that Balleau operates as a vector for precisely such a world: he holds within him the bloody storm of war and unleashes it upon these innocents.

And yet the teens – as we call them – are not, in the end, overly scarred by their encounter. They are called to enact relatively little violence, and indeed spend most of their time avoiding it. The final act of victory is not theirs but that of Balleu’s forsaken servant. And here we have another unexpected alignment with our earlier film The Vampire Bat.

When Von Niemann is killed at the end of The Vampire Bat it is not the police inspector who does the need, nor one of the handful of supporting characters: it is his own servant, the man he has been mind-controlling into bringing him victims. Both here and in Bloodlust there is an easy gloss of how evil is doomed to eat itself, that it is basically unsustainable and its own instruments will destroy it. That’s all well and good, but it’s perhaps not totally accurate.

Both films present as their villain someone who unwarrantedly assumes a necropolitical mantle – Von Niemann’s mad scientism and Balleau’s postwar bloodlust – but also suggest that these actions are self-effacing, rather than outgrowths of a basic power structure endemic to society. Neither the teens of Bloodlust nor the police inspector of The Vampire Bat must dirty their hands with necropolitics – by deciding and acting to kill their antagonists – because the basic fantasy that underpins both narratives is that we simply don’t have to, we are not a part of this system, and this system will deconstruct itself.

Indeed, both films argue that the servants of these systems will, in their final and noble moments, destroy them, losing their chains and their lives in one fell swoop and erasing the monstrous potential of their futurity. But what both narratives attempt to disavow – and yet, in some ways, must acknowledge if only by curious exclusion – is how the four white teens on an island vacation and the police inspector are themselves always already beneficiaries of a society in which scientific nihilism and postwar trauma have space to grow and fester, feeding off our lives even as our lives are fed by them.

This post is funded by readers like you through Patreon. If you like what you read, want to see me write more, and want to get a chance to choose what I write about, please consider pledging.