I missed last week’s blog because I was out of town for a graduation, and I might miss this week’s because I’ll be working on my current Shakespeare paper (it’s gonna be really cool, I promise). However, I’ve been trawling through my archives and I’ve found a paper I wrote three whole years ago on the horror manga of one Junji Ito. I’ve mentioned this before, back when I was singing the praises of Daniel Lau, renegade translator of many an Ito story otherwise unreadable by my paynim eyes. Incidentally, Lau is currently translating the long overdue Hellstar Remina, Ito’s saga of a Lovecraftian sci-fi apocalypse, and it’s silly as all get-out but very fun to read. It also makes very, very blatant some of the themes I teased out of Ito’s Uzumaki, which I still hold to be the current purest expression of his style and concerns.

So in case you haven’t read Uzumaki and you really want to, turn away now — go buy the books or borrow them or something. Read it, it’s worth it. If you have read it, then I’ve reproduced for you below my paper on the manga, which I think holds up surprisingly well. There are a few things I want to point out, though. One is that I read Uzumaki back in the day when our manga (if it was officially imported and translated at all) was flipped to read left to right, so all of my references to the comic are to these older editions — as I understand it, non-mirrored editions have since been released. The second point I’d like to make is that if this paper seems a bit weird and childish and very, very quotey, well, I was a college freshman when I wrote it. I’ve learned a thing or two since then.

So without further ado I give you…

A Vicious Spiral:

Enchanted Commodities and Cultural Narcissism in Junji Ito’s Uzumaki

Early in the first volume of Junji Ito’s horror manga Uzumaki, its protagonist Kirie Goshima, a high school girl, remarks, “I don’t think it’s that weird to be into spirals. I mean, there are people who collect much stranger things” (21). She is referring to Mr. Sato, the father of her boyfriend Shuichi. By this point the reader is well aware that Mr. Sato has recently become obsessed with collecting anything evoking a spiral pattern — sometimes spending hours staring at snail shells lying on the ground — and Shuichi is very unsettled. Both Kirie and the Sato family live in Kurozu-cho, a typical seaside community in Japan — a nation where “having a hobby or two is a big deal” (Kelts 158).

Fan culture in Japan is a unique beast; for example, until the term was appropriated by American fans of Japanese culture, Japan was the only nation that had otaku, or “people who live for their hobbies or interests” (Kelts 160). The closest equivalents were the American Star Trek fans, or Trekkies, but in Japan the idea was expanded: to be an otaku you do not have to be a fan of a particular television series, you simply have to be a fan. Certainly it may seem strange that Mr. Sato has become a spiral otaku, but in a country where people may develop intense fascinations with anthropomorphic personifications of computer operating systems, is liking a particular pattern or shape really that odd? Yet Kirie soon learns that Shuichi has every right to be upset. Not only is Mr. Sato’s spiral obsession dangerous, it’s contagious.

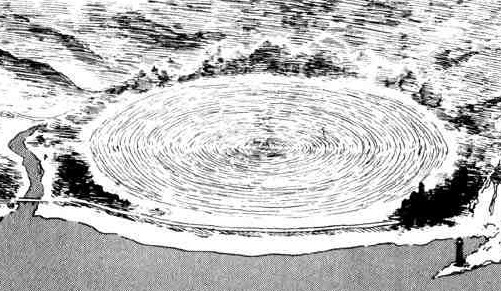

The choice of the Japanese word uzumaki is important. Despite being translated as “spiral” for the English release of the film based on the manga (and the manga’s English tagline, “Spiral into Horror”) a closer translation of uzumaki is ‘whirlpool’ (“Uzumaki”). Though whirlpools are often associated with the spiral shape, they have the unique property of actively drawing someone in; they are forces that pull people or things inexorably toward their center to sink or drown. This is integral to what may be seen as Ito’s critique of (to borrow a term from Anne Allison) “enchanted commodities,” a system where “play creatures … are packaged to feed a consumer fetishism that … penetrates the texture of ordinary life in ever more polymorphous ways” (Allison 16). This could easily describe the spiral obsession of Mr. Sato. Allison explains in Millennial Monsters that the polymorphous perverse pleasure “extends over multiple territories” and “can be triggered by any number of stimuli” (10).

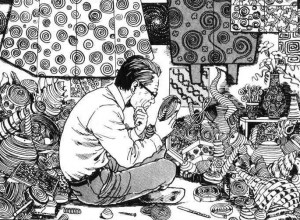

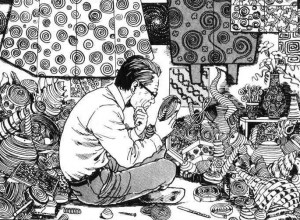

This is plainly displayed in the manga’s first volume: when Shuichi explains the extent of his father’s hobby, we see a panel showing Mr. Sato sitting in a room filled with spiral-shaped objects and objects adorned with spiral patterns (22). Mr. Sato’s consumer fetishism is focused on the shape (the spiral), while its actual form (incense coil, kimono fabric pattern, etc.) is irrelevant. The spiral could stand in for any possible quality that makes a commodity “enchanted” in the eyes of the consumer, be it a brand name or association with a particular character or mascot. Reading the manga this way, we see that these enchanted qualities can (drawing on the spiral’s iconographic connotations) disorient, confuse, and enthrall, inexorably drawing the consumer deeper into a frenzy of collection.

In Roland Kelts’ book Japanamerica, he claims that one of the reasons Japanese pop culture is so successful both in its native country and abroad is that “fandom is participatory, and communal” — what Kelts calls “the do-it-yourself (DIY) factor” (147). Fans of a particular anime or manga, for example, will fashion their own costumes after the outfits of their favorite characters (‘costume play’ or cosplay), while other fans may write and draw their own doujinshi — fan-made manga using characters from the amateur artist’s own favorite series.

The fans that make the most accurate costumes or most entertaining doujinshi gain a favorable reputation among other fans and garner interest in the original anime or manga, expanding the consumer base and at the same time producing more fans, who will create their own content and continue the cycle. Uzumaki has its own sardonic take on this DIY factor in the first volume: when Shuichi’s mother, concerned because her husband has stopped going to work, throws away the entire spiral collection, Mr. Sato is at first furious, then smug. “I don’t care,” he utters, before screaming: “I don’t need to collect spirals anymore! I finally realized that you can make spirals yourself! You’ll see! You can express the spiral through your own body!” (29, my italics in both cases).

The fans that make the most accurate costumes or most entertaining doujinshi gain a favorable reputation among other fans and garner interest in the original anime or manga, expanding the consumer base and at the same time producing more fans, who will create their own content and continue the cycle. Uzumaki has its own sardonic take on this DIY factor in the first volume: when Shuichi’s mother, concerned because her husband has stopped going to work, throws away the entire spiral collection, Mr. Sato is at first furious, then smug. “I don’t care,” he utters, before screaming: “I don’t need to collect spirals anymore! I finally realized that you can make spirals yourself! You’ll see! You can express the spiral through your own body!” (29, my italics in both cases).

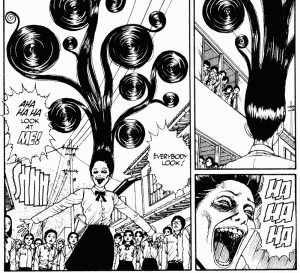

Almost immediately after this outburst Mr. Sato removes his glasses and begins to roll his eyes — each moving in opposite directions. The body horror escalates: in a second encounter, Mr. Sato shows Kirie that he can now extend his tongue inhumanly far and curl it into a spiral shape and, following the man’s death, Shuichi reveals that his father committed suicide by crawling into a round barrel and contorting himself into a spiral, breaking every bone in his body. In a darkly humorous fashion, Mr. Sato’s death might be considered the ultimate form of cosplay: he truly becomes his obsession, rather than simply dressing up as it. Even when his body is cremated, the smoke of Mr. Sato’s ashes forms a spiral cloud in the sky.

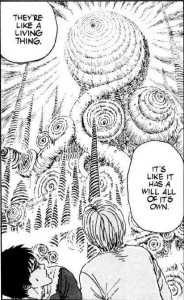

But, as Kelts says, Japanese fandom is communal — and so is Ito’s analogue for it, the spiral obsession. Shuichi’s mother, following her husband’s death, develops an intense fear of spirals; every time she sees one, she only sees her husband’s grotesque body and hears his voice begging her to “join [him] in the spiral” (Ito, Volume One 53). She removes all spirals from her body by shaving off her hair, cutting off the tips of her fingers to remove the prints, and finally stabbing herself to remove the spiral-shaped cochlea of her inner ear. She dies soon thereafter, having destroyed her sense of balance and, for the short remainder of her life, experiencing a permanent sense of spinning vertigo — “I don’t want to become a spiral!” she protests (Volume One 74). Following cremation, her body’s ashes also form a spiral cloud. With her death it seems the floodgates are thrown open and the spiral obsession is loosed upon Kurozu-cho in full force. Soon, Kirie and Shuichi are forced to deal with multiple bizarre situations where people “become” spirals or “express” the spiral through their bodies.

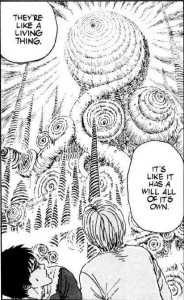

The strange way in which the spirals themselves seem to be alive and in which people seem to become spirals is informed by two particular facets of the Japanese mindset. The first, drawing on a history of Shintoist animism, is “a tendency to see the world as animated by a variety of beings, both worldly and otherworldly, that are complex, (inter)changeable, and not graspable by so-called rational (or visible) means alone” (Allison 12). In Ito’s world, the spirals are an ancient, incomprehensible force; roughly halfway through the third volume, Kirie finds an ancient map in an equally old Japanese-style row house. Drawn in the place of Kurozu-cho is an immense spiral, implying that the spiral obsession has its roots in the distant past and is, in fact, part of the city’s very foundation or the environment itself.

Similarly, the act of “becoming” a spiral reflects a Japanese predilection for morphing and transformation in media, fostered in the wake of the country’s defeat in World War II and the appearance of “unstable and shifting worlds where characters, monstrously wounded by violence and collapse of authority, reemerge with reconstituted selves” (Allison 12). In recent times this morphing has become a positive attribute with such franchises as the Super Sentai series, but in Uzumaki Ito utilizes transformation in a much more negative way, reminiscent of the post-war Gojira: the people of Kurozu-cho appear to mutate into destructive, mindless beasts. These concepts of animism and mutability come together in Uzumaki’s gloomy finale.

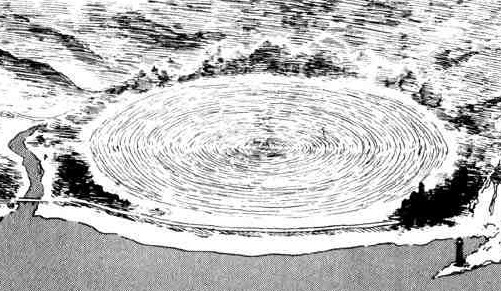

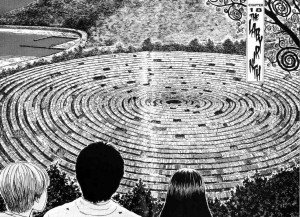

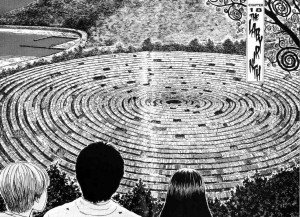

Kurozu-cho has been decimated, leaving the old row houses as the only shelters, and in visuals the landscape mimics a war zone. In the wake of this pseudo-atomic bomb blast, the people of the city begin rebuilding their lives, just as the Japanese attempted to rebuild following WWII. However, the survivors have begun a process of expansion, linking the old buildings as one superstructure in — of course — the form of a giant spiral, beginning at the edge of town and stopping at a pond in Kurozu-cho’s center. As Kirie and Shuichi soon discover, the people living in these row houses are no longer human in the strictest sense of the word: they still speak like human beings, yes, but a combination of living in close quarters and malign supernatural influences have transformed them into slimy, genderless, boneless creatures whose limbs have twined and looped together in a seemingly infinite mass.

When Kurozu-cho’s pond drains (in a clear echo of the uzumaki or whirlpool of the title), it reveals a strange spiral staircase leading down into the earth, and the massive interconnected swirl of former humans gleefully slides out of their row house en masse. Kirie and Shuichi follow and discover, miles beneath Kurozu-cho, an eldritch city of stone spiral towers. Shuichi remarks that it feels as if the ruins are alive and watching him: “It’s like it’s cursing us for being underground, hidden from all the eyes up there” (Volume Three 214).

The countless people from Kurozu-cho who litter the ground stare blankly into the spiral city, and Kirie notes that they seem to be turning to stone. Shuichi continues: “I don’t know who… or what built it here, or why… but every so often, every few hundreds, or thousands, or tens of thousand years, it can reach the people above ground. And even though its builders are gone… maybe it’s still building itself” (Volume Three 214). The petrified half-humans with their distended, looping, spiraling bodies appear to be the living city’s latest additions, new building blocks to fuel its infinite growth. Shuichi, who has been injured in a fall, orders Kirie to leave him and escape to the surface. She refuses, choosing instead to embrace Shuichi, and as they lay together on the stones that used to be their neighbors, the couple’s arms and legs begin to twist together. The animate stone city draws people to it and morphs them into an extension of itself: every citizen of Kurozu-cho has had his or her obsession satisfied and has finally become part of the spiral.

The countless people from Kurozu-cho who litter the ground stare blankly into the spiral city, and Kirie notes that they seem to be turning to stone. Shuichi continues: “I don’t know who… or what built it here, or why… but every so often, every few hundreds, or thousands, or tens of thousand years, it can reach the people above ground. And even though its builders are gone… maybe it’s still building itself” (Volume Three 214). The petrified half-humans with their distended, looping, spiraling bodies appear to be the living city’s latest additions, new building blocks to fuel its infinite growth. Shuichi, who has been injured in a fall, orders Kirie to leave him and escape to the surface. She refuses, choosing instead to embrace Shuichi, and as they lay together on the stones that used to be their neighbors, the couple’s arms and legs begin to twist together. The animate stone city draws people to it and morphs them into an extension of itself: every citizen of Kurozu-cho has had his or her obsession satisfied and has finally become part of the spiral.

But in Japan, where it is not at all uncommon to see in fiction “a universe where the borders between thing and life continually cross and intermesh” (Allison 13), why is Uzumaki horrifying? Why is its morphing scary and unsettling, while the morphing of the Super Sentai series is one of the largest parts of the program’s appeal? I believe the answer may lie in the horrific themes of narcissism. The old horror story is generally a tale of punishment for unexpiated sin, but as American critic John G. Parks observed in 1978, “Nearly all characters [of the modern horror story] are narcissistic.” In 1979, cultural historian Christopher Lasch published The Culture of Narcissism, in which he argued that late-capitalist society had bred a generation of Americans suffering from pathological narcissism.

Contrary to egotistical narcissists, pathological narcissists have a weak sense of self and attempt to establish it in any way possible (thus appearing, in many ways, akin to typical narcissists); Lasch insists that this type of narcissism “has more in common with self-hatred than with self-admiration” (31). He also lists the signs indicating a pathologically narcissistic personality; of particular importance for this paper is his tenth: “fascination with celebrity.” Though both Parks and Lasch are Americans writing about American issues, their observations may ring true for Japanese society, as well.

Currently the Japanese people are becoming increasingly individualistic, increasingly atomized; as Allison says, when describing what she calls “solitarism” and its relation to enchanted commodities, “people seek out companionship, but ironically (or not), the form this often takes is …. a machine or toy purchased with money that is wired into the (individual) self” (14). By the end of Uzumaki, the people of Kurozu-cho are glad to become part of the spiral, something larger than themselves, even though the thing they have become a part of is monstrous. Lasch draws links between pathological narcissism and extremist cult activity in the US (98); one may compare this with the 1995 Sarin gas subway attacks carried out by the sizeable Japanese cult Aum Shinrikyo.

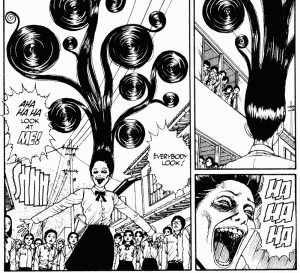

Japan is also a culture of celebrities, with music idols and seiyuu becoming objects of fixation for thousands of fans. A criticism of this culture is palpable in almost all of Ito’s work, and we find it reflected slyly in Uzumaki: in the first volume, a girl’s hair becomes animate and demands attention from those around her, hypnotizing them and displaying its curls for hours, but it also drains her strength and kills her, becoming more or less an independent entity. In the second volume, a black lighthouse with a strange spiraling beacon entrances all those who look see it; in the third volume, the reason Shuichi hypothesizes for the spiral city’s evil is its anger at being hidden away from all those who would see it. The spirals (that is, the enchanted commodities) are living creatures that demand attention; the pathologically narcissistic people of Kurozu-cho can provide this attention, but also crave it for themselves. Collecting is no longer enough, so they sacrifice themselves to the spirals — they become the spirals — in the maximum display of devotion and in hopes of receiving attention from others.

palpable in almost all of Ito’s work, and we find it reflected slyly in Uzumaki: in the first volume, a girl’s hair becomes animate and demands attention from those around her, hypnotizing them and displaying its curls for hours, but it also drains her strength and kills her, becoming more or less an independent entity. In the second volume, a black lighthouse with a strange spiraling beacon entrances all those who look see it; in the third volume, the reason Shuichi hypothesizes for the spiral city’s evil is its anger at being hidden away from all those who would see it. The spirals (that is, the enchanted commodities) are living creatures that demand attention; the pathologically narcissistic people of Kurozu-cho can provide this attention, but also crave it for themselves. Collecting is no longer enough, so they sacrifice themselves to the spirals — they become the spirals — in the maximum display of devotion and in hopes of receiving attention from others.

Even though Parks and Lasch are Americans, they both managed to describe certain cultural facets that fit almost perfectly into Uzumaki, leading me to believe that, in the era of globalization, our horror stories are also becoming globalized. A lot can be deduced about a culture from its monsters, and the fact that American and Japanese monsters are becoming more similar (the influence of Japanese horror cinema is notable in today’s American film market) implies a greater closeness of culture than ever before, perhaps brought about by both countries’ late-stage capitalism and aided, as Kelts fancies, by a similar sense of tragedy felt by the Japanese over the atomic bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima and by Americans over the September 11 attacks (37).

However, despite its growing numbers of “otaku,” despite its own enchanted commodities, despite its acceptance of morphing characters, the US apparently lacks the animist context of Japanese culture that helps completely decipher Ito’s bizarre plot. Americans are also, perhaps, still too insistent on happy endings and solid resolution; the mono no aware of Ito’s ending is definitely not suited to American tastes. Uzumaki isdefinitely a Japanese work, made from a Japanese viewpoint and with Japanese readers in mind; nevertheless, its warning against the possible dangers of asserting one’s own weak personality by consuming supposed enchanted commodities, or by becoming the center of attention, or by becoming something bigger than oneself, rings true in a way that may speak to both Japanese and American readers.

In our current climates of aging capitalism, both nations travel on increasingly similar paths: paths of consumerism and narcissism that, as Ito might have it, curve inexorably inward toward a center, toward a single point — a dead end.

List of Works Cited

Allison, Anne. Millennial Monsters. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006.

Ito, Junji. Uzumaki, Volume One. Trans. Yuji Oniki. 2001. San Francisco: Viz Communications, Inc, 2003.

—. Uzumaki, Volume Two. Trans. Yuji Onki. San Francisco: Viz Communications, Inc, 2002.

—. Uzumaki, Volume Three. Trans. Yuji Onki. San Francisco: Viz Communications, Inc, 2002.

Kelts, Roland. Japanamerica: How Japanese Culture Has Invaded the US. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

Lasch, Christopher. The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Experience. 1979. New York: Norton, 1991.

Parks, John G. “Waiting for the End: Shirley Jackson’s The Sundial.” Critique, Vol. XIX, No. 3, 1978.

“Uzumaki.” Random House Japanese-English English-Japanese Dictionary. 1995. New York: Random House. 1997.

The fans that make the most accurate costumes or most entertaining doujinshi gain a favorable reputation among other fans and garner interest in the original anime or manga, expanding the consumer base and at the same time producing more fans, who will create their own content and continue the cycle. Uzumaki has its own sardonic take on this DIY factor in the first volume: when Shuichi’s mother, concerned because her husband has stopped going to work, throws away the entire spiral collection, Mr. Sato is at first furious, then smug. “I don’t care,” he utters, before screaming: “I don’t need to collect spirals anymore! I finally realized that you can make spirals yourself! You’ll see! You can express the spiral through your own body!” (29, my italics in both cases).

The fans that make the most accurate costumes or most entertaining doujinshi gain a favorable reputation among other fans and garner interest in the original anime or manga, expanding the consumer base and at the same time producing more fans, who will create their own content and continue the cycle. Uzumaki has its own sardonic take on this DIY factor in the first volume: when Shuichi’s mother, concerned because her husband has stopped going to work, throws away the entire spiral collection, Mr. Sato is at first furious, then smug. “I don’t care,” he utters, before screaming: “I don’t need to collect spirals anymore! I finally realized that you can make spirals yourself! You’ll see! You can express the spiral through your own body!” (29, my italics in both cases).

The countless people from Kurozu-cho who litter the ground stare blankly into the spiral city, and Kirie notes that they seem to be turning to stone. Shuichi continues: “I don’t know who… or what built it here, or why… but every so often, every few hundreds, or thousands, or tens of thousand years, it can reach the people above ground. And even though its builders are gone… maybe it’s still building itself” (Volume Three 214). The petrified half-humans with their distended, looping, spiraling bodies appear to be the living city’s latest additions, new building blocks to fuel its infinite growth. Shuichi, who has been injured in a fall, orders Kirie to leave him and escape to the surface. She refuses, choosing instead to embrace Shuichi, and as they lay together on the stones that used to be their neighbors, the couple’s arms and legs begin to twist together. The animate stone city draws people to it and morphs them into an extension of itself: every citizen of Kurozu-cho has had his or her obsession satisfied and has finally become part of the spiral.

The countless people from Kurozu-cho who litter the ground stare blankly into the spiral city, and Kirie notes that they seem to be turning to stone. Shuichi continues: “I don’t know who… or what built it here, or why… but every so often, every few hundreds, or thousands, or tens of thousand years, it can reach the people above ground. And even though its builders are gone… maybe it’s still building itself” (Volume Three 214). The petrified half-humans with their distended, looping, spiraling bodies appear to be the living city’s latest additions, new building blocks to fuel its infinite growth. Shuichi, who has been injured in a fall, orders Kirie to leave him and escape to the surface. She refuses, choosing instead to embrace Shuichi, and as they lay together on the stones that used to be their neighbors, the couple’s arms and legs begin to twist together. The animate stone city draws people to it and morphs them into an extension of itself: every citizen of Kurozu-cho has had his or her obsession satisfied and has finally become part of the spiral. palpable in almost all of Ito’s work, and we find it reflected slyly in Uzumaki: in the first volume, a girl’s hair becomes animate and demands attention from those around her, hypnotizing them and displaying its curls for hours, but it also drains her strength and kills her, becoming more or less an independent entity. In the second volume, a black lighthouse with a strange spiraling beacon entrances all those who look see it; in the third volume, the reason Shuichi hypothesizes for the spiral city’s evil is its anger at being hidden away from all those who would see it. The spirals (that is, the enchanted commodities) are living creatures that demand attention; the pathologically narcissistic people of Kurozu-cho can provide this attention, but also crave it for themselves. Collecting is no longer enough, so they sacrifice themselves to the spirals — they become the spirals — in the maximum display of devotion and in hopes of receiving attention from others.

palpable in almost all of Ito’s work, and we find it reflected slyly in Uzumaki: in the first volume, a girl’s hair becomes animate and demands attention from those around her, hypnotizing them and displaying its curls for hours, but it also drains her strength and kills her, becoming more or less an independent entity. In the second volume, a black lighthouse with a strange spiraling beacon entrances all those who look see it; in the third volume, the reason Shuichi hypothesizes for the spiral city’s evil is its anger at being hidden away from all those who would see it. The spirals (that is, the enchanted commodities) are living creatures that demand attention; the pathologically narcissistic people of Kurozu-cho can provide this attention, but also crave it for themselves. Collecting is no longer enough, so they sacrifice themselves to the spirals — they become the spirals — in the maximum display of devotion and in hopes of receiving attention from others.