Hello to anyone who’s stumbled this way from Professor Brainworm’s blog! I hope you’ll bear with me, since I can be pretty longwinded. Anyway.

Our journey through the wonderful world of Bret Ellis’s novel American Psycho thus far could be summed up in the following way if it were a game of Clue: Shakespeare’s Macbeth in Dante’s Inferno with Reagan’s Manhattan. Today on the ominously dubbed Black Friday, I’ll finish up my little ramble. I plan to for a rebuttal to the issue that, after the explicit pornography and violence, is the most challenged aspect of the novel: its nihilism.

I encountered something like this when I first read the book when I was 14. You’ll recall I took it as a straight satire, and so in the end I didn’t feel like it had accomplished the actual goal of satire: I didn’t know what better lifestyle was possible, because in the novel if you are not Patrick Bateman then you are one of his shallow friends or a homeless person, and none of these options are very good. But as I’ve said, Psycho is not a satire. It has satiric elements, certainly, in a similar way the recent film version of New Moon inexplicably has a scene that satirizes modern Hollywood action films. Bret Ellis’s satire is much more deft, of course, and much more regularly implemented; it’s not a one-off scene, but a large part of the text. Yet it is not, as we may be tempted to think, the heart of the text.

The heart is salvation.

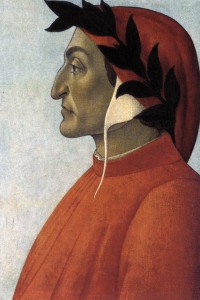

Rewritings of Dante are always about salvation in the same way sonnets are always about love. A traditional if boring sonnet is one that lists, without irony, the traditional values that make a loved one, well, loved. An exciting sonnet is one that talks about how love is impossible, a lie, fake, a delusion — but even when it tries to negate those things, it is still a poem about love. Similarly, a traditional rewriting of Dante is going to be about a dude going through some hardship, suffering, and becoming a better person in the end. An exciting rewriting of Dante, like American Psycho, is going to pull the same trick as the not-about-love sonnet: it will try say that salvation does not exist, is impossible. But the idea of salvation is still there, lurking behind every venomous negation, and sometimes — sometimes — it manages to glitter through.

The pattern is pretty straightforward in Dante. Dante and Virgil travel through Hell in Inferno, where they see the consequences of sin, and then move onward to the Mountain of Purgatory in Purgatorio. Purgatory, of course, being the place where sins are purged from the soul prior to entering Heaven. To enter Purgatory, however, they have to pass by a robed angel who guards the gate; Virgil urges Dante to beg the angel to let him enter, and the following transactions occur:

Devoutly prostrate at his holy feet,

I begged in mercy’s name to be let in,

but first three times upon my breast I beat.Seven P‘s, the scars of sin,

his sword point cut into my brow. He said:

“Scrub off these wounds when you have passed within.”Canto IX, 109-114

Each of the seven P‘s on Dante’s forehead represents one of the seven cardinal sins that Purgatory is supposed to rid him of; after passing through each circle one disappears and Dante feels lighter.

If you’re in any way religious — particularly if you are Catholic — this may have echos of Ash Wednesday. If you’re a godless heathen, then the short of it is that Ash Wednesday is the first day of Lent, the period of penitence and fasting leading up to Easter. On Ash Wednesday, the penitents are marked by the priest with a cross of ashes on the forehead, a reminder that human beings come from dust and, but for the grace of God, they’ll someday be to the dust returned. In other words, it’s a humbling process, just as the journey through Dante’s Purgatory is meant to humble those souls that were sinful in life but not beyond hope.

If you’re in any way religious — particularly if you are Catholic — this may have echos of Ash Wednesday. If you’re a godless heathen, then the short of it is that Ash Wednesday is the first day of Lent, the period of penitence and fasting leading up to Easter. On Ash Wednesday, the penitents are marked by the priest with a cross of ashes on the forehead, a reminder that human beings come from dust and, but for the grace of God, they’ll someday be to the dust returned. In other words, it’s a humbling process, just as the journey through Dante’s Purgatory is meant to humble those souls that were sinful in life but not beyond hope.

Now that’s all well and good, you’re saying, but what in the hell does Ash Wednesday have to do with American Psycho?

Since there’s nothing I like more than tossing away conclusions I’ve already made, think back on our initial reading of the Inferno influence on Psycho in Part 2. We mapped out a set of relationships between the characters to mirror that of the Comedy’s Dante-Virgil-Beatrice triad, and our best Virgil candidate was a sort-of-friend of Patrick Bateman’s named Timothy Price. He’s like Virgil, I said, because he’s the most interesting person Bateman knows, someone he seems to admire in a really odd but genuine way, the closest thing Bateman has to a friend, and he leaves Patrick before the end of the novel.

But Tim Price is unlike Virgil in one very important way: he comes back.

….[F]or the sake of form, Tim Price resurfaces, or at least, I’m pretty sure he does. While I’m at my desk simultaneously crossing out the days in my calendar that have already passed and reading a new best seller about office management called Why It Works to Be a Jerk, Jean buzzes in, announcing that Tim Price wants to talk, and I fearfully say, “Send him… in.” Price strolls into the office wearing a wool suit by Canali Milano, a cotton shirt by Ike Behar, a silk tie by Bill Blass, cap-toed leather lace-ups from Brooks Brothers. I’m pretending to be on the phone. He sits down, across from me, on the other side of the Palazetti glass-top desk. There’s a smudge on his forehead or at least that’s what I think I see.

…

“You’ve been gone, like, forever, Tim. What’s the story?” I ask, again noticing the smudge on his forehead, though I get the feeling that if I asked someone else if it was truly there he (or she) would just say no. (p.383-384)

Price disappears within the first 60 pages of the novel and returns in the last 20. After he ran off into the fake train tunnel in the club, he has not been mentioned at all — but suddenly here he is, with a peculiar smudge on his forehead. The chapter he reappears in is called Valentine’s Day, which is on February 14th, and it so happens that this part of the novel takes place in 1989, when Ash Wednesday fell on February 8th.

I’m sure you see what I’m driving at.

So Price, when he returns, comes in the form of someone penitent — or at least that’s how Bateman feels. We know he’s prone to hallucinating, and here he openly questions whether or not he actually sees the smudge. Nevertheless, we know that Price is someone Bateman admires — “I’m wondering and not wondering what happens in the world of Tim Price, which is really the world of most of us: big ideas, guy stuff, boy meets world, boy gets it” (384). There is something about Price, some spirit or personality or agency, that Patrick sees as lacking in himself; suddenly it makes a whole lot of sense why the opening paragraph I quoted in Part 2 almost makes it seem like the novel is going to be a third-person narration about Tim Price, but is actually just Patrick thinking about Tim Price.

So what is it Price has that Bateman doesn’t? In Part 3 I said Bateman’s chief sin is that of despair — he does not think the world can be made better, and his only attempts to even try are simply gross, violent parodies of the shallowness and greed he sees all around him. Price, it would seem, is not a victim of this despair. He’s just as rich and shallow as Patrick, just as obnoxious, but in the scene at Tunnel when he becomes fed up with the empty life he leads he doesn’t just lapse into a murderous frenzy (or fantasy) like Patrick seems to have done. Instead, he actually tries to get out, something Patrick has never attempted — something that he is, in fact, probably afraid to do.

Is Price actually on his way to salvation? After all, he left, but he came back. His first conversation with Bateman may — just possibly may — imply that he is looking for girls to hook up with, since he asks Patrick for the number of a woman they both know who is in a relationship with a mutual acquaintance. Like Patrick, we can’t be sure if Price is really penitent, and we don’t see much of him at all until the very last chapter, the one that ends with Patrick reading the NO EXIT sign.

Bateman and some of his friends, including Price, go out to a club.

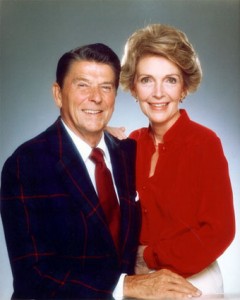

On the [TV] screen now are scenes from President Bush’s inauguration early this year, then a speech from former President Reagan, while Patty [the talk show host] delivers commentary. Soon a tiresome debate forms over whether he is lying or not, even though we don’t, can’t, hear the words. The first and really only one to complain is Price, who, though I think he’s bothered by something else, uses the opportunity to vent his frustration, looks inappropriately stunned, and asks, “How can he lie like that? How can he pull that shit?”

“Oh Christ,” I moan. “What shit? Now where do we have reservations at? I mean I’m not really hungry but I’d like to have reservations somewhere.” (p. 396)

And from that, the conversation devolves into everyone arguing about where to eat, Price’s concerns left unaddressed. Even if something else seems to be bothering Price, he does seem to have a bone to pick with Reagan — what was he lying about? What sort of shit is he getting away with? I wasn’t watching much TV back then, but one possibility is that Reagan is speaking about the 1989 IRS investigation of him and his wife Nancy for unpaid taxes on various gifts they received while in the White House. It was eventually determined that the Reagans owed three million dollars on “fashion items” (to quote Wikipedia) that had been given to Nancy.

And from that, the conversation devolves into everyone arguing about where to eat, Price’s concerns left unaddressed. Even if something else seems to be bothering Price, he does seem to have a bone to pick with Reagan — what was he lying about? What sort of shit is he getting away with? I wasn’t watching much TV back then, but one possibility is that Reagan is speaking about the 1989 IRS investigation of him and his wife Nancy for unpaid taxes on various gifts they received while in the White House. It was eventually determined that the Reagans owed three million dollars on “fashion items” (to quote Wikipedia) that had been given to Nancy.

Reagan here represents the freewheeling economic attitude and casual greed that characterize Ellis’s portrait of the decade, the broad symbol of the lives that all of the horrible characters in the novel lead, and it is only Price who questions him. And it’s Patrick, bored and uninterested, who changes the subject.

Price looks away from the television screen, then at Craig, and he tries to hide his displeasure by asking me, waving at the TV, “I don’t believe it. He looks so… normal. He seems so… out of it. So… undangerous.”

“Bimbo, bimbo,” someone says. “Bypass, bypass.”

“He is totally harmless, you geek. Was totally harmless. Just like you are totally harmless. But he did do all that shit and you have failed to get us into 150, so, you know, what can I say?” McDermott shrugs.

“I just don’t get how someone, anyone, can appear that way and yet be involved in such total shit,” Price says, ignoring Craig, averting his eyes from Farrell. He takes out a cigar and studies it sadly. To me it still looks like there’s a smudge on Price’s forehead.

“Because Nancy was right behind him?” Farrell guesses, looking up from the Quotrek. “Because Nancy did it?”

“How can you be, I don’t know, so fucking cool about it?” Price, to whom something really eerie has obviously happened, sounds genuinely perplexed. Rumor has it he was in rehab.

…

“Oh brother.” Price won’t let it die. “Look,” he starts, trying for a rational appraisal of the situation. “He presents himself as a harmless old codger. But inside…” He stops. My interest picks up, flickers briefly. “But inside…” Price can’t finish the sentence, can’t add the last two words he needs: doesn’t matter. I’m both disappointed and relieved for him. (p. 397)

Here we see that the sort of will Bateman perceives in Price is not a delusion — it’s real. Price has the ability to change, he has the desire; only he is offended that a person in power lies, cheats, and steals. Only he’s been to rehab, only he wears the phantasmagorical smudge of the penitent. His description of Reagan as a harmless-looking man never seems to finish, perhaps because it frightens him: Reagan can look like an old movie star, an aw shucks nice guy, but within him dwells the capacity for cruel and casual evil. Bateman is the same way: he looks normal, but there is something terrible inside of him, something he has decided to stop fighting, and that is why he finishes the sentence in a way Price probably wouldn’t agree with: he claims that what’s inside doesn’t matter. Price’s gradual realization seems to be moving in the opposite direction, the idea that the inside does matter. Success has a greater dimension than economics, than wealth and power and being physically attractive; it is a moral and spiritual matter.

Remember that the beginning of the story makes it seem like Price will be the main character — we are told what he is doing, who he is, we are told that he notices the words ABANDON ALL HOPE YE WHO ENTER HERE. And now here we see him beginning to understand how life should be lived — with honesty and compassion. Timothy Price is the Dante figure here, and he’s traveled through Hell and seen the results of a sinful life; now he’s penitent, the ash is on his brow, and it is his responsibility to cleanse himself, to work toward a more honest and compassionate life.

We don’t know for sure if he does — he’s a little afraid, as Patrick notes — but the fact that he can do this makes all the difference. There is an exit, but it’s not easy to get to and even more difficult to pass through. It’s a path Bateman doesn’t want to acknowledge, and thus he is damned. He’s not Dante, and he’s not Virgil; he’s one of the screaming shades, tortured for eternity in Hell, punished in accordance to the decisions he’s made in life.

In a purely aesthetic sense, this is why I think American Psycho is a great novel: it is well written — extremely well written, in fact, and though Patrick Bateman’s endless recitation of brands and clothing lines may get grating, it’s also an inextricable part of his character, a fundamental element of his voice and his psychology. The novel is also, I think, in meaningful dialogue with other works of literature that have come before it — it shows us how Macbeth may play out in the modern day, the unassuming madman, and it turns Dante on his head by showing us how one can so easily despair into Hell, or Hell on Earth.

In a more personal and moral sense, this is why I think American Psycho is a great novel: It tells us something very profound and very important about human existence — not how to live in an obvious, satirical way, but more in the sense of what it is like to live. We are surrounded on all sides by greed, cruelty, injustice, and horror; in such an environment it may seem like there’s nothing to do but give up, to become greedy and cruel and unjust and horrific in our own turn, and while that is always a possibility it is never the only choice. There is a moral way to live, a good way to live, a better way to live; the trick is to remember that it exists, even when so many people around you don’t believe it.

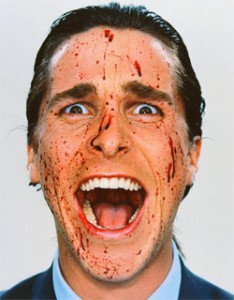

And this is why I think that American Psycho is a great horror novel: Obviously the reasons above apply, horror should not be above the requirements for something to be a piece of literature, it should be well written and canonically articulate. But it actually adds another criterion: a horror novel has to be scary.

There are two types of scary, as far as I am concerned. One is the splatterpunk approach, graphic violence for violence’s sake, gallons of gore that gross you out, make you feel like barfing. The thing about this type of horror is that it doesn’t last, it’s too physical, too visceral; it’s also, unfortunately, the more popularized part of American Psycho. Yes, splatterpunk is here — loads of it, in fact, and yeah, it’s gross as hell and effective for what it is. But there’s something more clever than that at work, too: the second type of horror, what you might call metaphysical horror or philosophical horror, the sense of fear and unease resulting from the sudden realization that the world does not function according to whatever rules you take for granted and the universe might be, in fact, a much more dangerous and inhospitable place than you believed.

Bret Ellis combines both splatterpunk and philosophical horror by making Patrick Bateman so unreliable. Whether or not he commits the murders is unimportant in the splatterpunk sense, because the descriptions of them are just as graphic and gut-churning. But the fact that these may all be fantasies — that Patrick is just some hopeless, repressed guy living out psychotic daydreams behind an ordinary exterior — takes it to another level. Suddenly everything is thrown into question. I’m thinking of a part near the end of the novel, where Patrick mentions his housekeeper coming into his apartment and cleaning bloodsplatter off the walls and floor — as if it didn’t matter, as if it weren’t a problem for her at all. If the blood is really there, is the maid keeping her mouth shut just to save herself, or does she simply not care enough to report Bateman? If Bateman is making it all up, how many people do you meet every day are just like him? How many repressed psychotics walk among us? If Patrick isn’t lying, if he does some or all of the things he claims to, then how believable is it? Do we live in a society so disconnected, so unfeeling, that we would just allow this stuff to happen so long as we didn’t have to deal with it?

The cannibalism and rape make you queasy, and the implications make you uneasy. You can forget about all of the murders in time, but can you get rid of the nagging question: How does the world work?

To answer that is to overcome or make peace with the philosophical horror the novel instigates. The easiest way to read the book is to say that yes, the world is cruel and senseless and evil and no one cares, the world is terrible and we are all trapped in it and THIS IS NOT AN EXIT. But I hope that over the past few weeks I’ve shown that there is another answer. Sure, it’s small and difficult to find, requiring a careful and thoughtful reading of the text, but it’s there.

There is hope; there is possibility; there is salvation; there is, in fact, an exit.

To put it quickly and simply, Pat Bateman is Macbeth. It’s so cleverly updated, I think, that it’s pretty easy

To put it quickly and simply, Pat Bateman is Macbeth. It’s so cleverly updated, I think, that it’s pretty easy to miss: one of Macbeth’s defining early characteristics is his insecurity, so Bateman constantly obsesses over what he is wearing in comparison to what everyone else is wearing, which stereo system is the best or most expensive and can he get one, and in one scene practically has a panic attack when he sees that a colleague has a more stylish business card. And just as Macbeth is prone to seeing things, so is Bateman, who imagines that Satan is speaking to him through Bono at a U2 concert, an anthropomorphic Cheerio is being interviewed on his favorite sensationalist talk show, a park bench is stalking him, and, in a scene launched into the general pop culture by the film version, an ATM wants him to feed it a stray cat.

to miss: one of Macbeth’s defining early characteristics is his insecurity, so Bateman constantly obsesses over what he is wearing in comparison to what everyone else is wearing, which stereo system is the best or most expensive and can he get one, and in one scene practically has a panic attack when he sees that a colleague has a more stylish business card. And just as Macbeth is prone to seeing things, so is Bateman, who imagines that Satan is speaking to him through Bono at a U2 concert, an anthropomorphic Cheerio is being interviewed on his favorite sensationalist talk show, a park bench is stalking him, and, in a scene launched into the general pop culture by the film version, an ATM wants him to feed it a stray cat.

As it turns out, quite a lot. Let’s take a look at the very beginning of Ellis’s novel:

As it turns out, quite a lot. Let’s take a look at the very beginning of Ellis’s novel: