At the beginning of 2010 I spent a few months studying abroad in London. I lived in North London in the Hampstead area, with a roommate, in the home of a host family. I’ll call my host parents Clarence and Emma. They were both semiretired doctors in their early 70s; their three daughters had long ago moved out, gotten married, and had their own children. Their (Clarence and Emma’s) home was the sort of sandwiched townhouse you see all over London. Of course, C&E being semiretired doctors and this being Hampstead, within spitting distance of the Heath, it was actually a nice place and, as you might imagine, really, really old.

It was a Victorian building, but had been remodeled several times, with electricity and phone lines and everything. Clarence and Emma bought the house in the 60s, just after it had been refurbished — the right side of it was damaged in the Blitz, and in fact the next three or four houses in the row had been entirely demolished and replaced with ugly, utilitarian flats.

Of course nothing strange happened right off the bat. I arrived at the beginning of January, and the weirdest thing at the time was that London was going through its first snowstorm in 30 years. Being from the rural American Midwest, it was endearing to me to see Londoners struggle with like two inches of snowfall, but that’s beside the point.

I’d never been outside of the country up until then, and never been away from home for more than a few weeks at a time (I’m astonishingly sheltered), so I spent a while adjusting to my new surroundings. Clarence and Emma had been hosting college students from the US for a few decades by then, and I found a bunch of papers a past student (a girl from Arizona, I gathered) had left in one of my desk drawers. One of the papers was a sort of strange checklist of reminders. I ended up taping it to the wall where I could always see it, since it seemed like an odd bit of found poetry. I still have it, actually — here’s what it says:

– notify bank of leave

– passport copies, extra pictures

– Friday!!! arrive at 5:35

– Saturday sightseeing

– Sunday sightseeing

– Monday classes begin

– toilets = restrooms

– plaster = bandaid

– servillette = napkin

– do not tip, considered an insult

– stay with friends when going out

– do not forget things — they will be gone

So yeah I am pretty much a melancholy jackass. But after a while I began to come around, I got used to my classes, to taking the tube in the mornings, I got used to the rhythms of the city. It happened that I had a cousin who was studying in Stratford-upon-Avon, and she’d met a guy there and they were heading over to America soon to get married. I was invited up to Stratford for their sort of pre-wedding reception for all their UK friends, as the sole representative of her side of the family.

About two weeks after arriving in London, the weekend of this reception comes and I head off from Marylebone, have a high time with Stratford, make new friends, be a Shakespeare geek, and so on. It was a cold, rainy day — and remember, it’s snowed in London for the first time in 30 years. Ice all over the damn place is the obvious result. My train out of Stratford was supposed to leave at 9:30, but it ended up delaying until 10:30. Then, while on the train, the rain turned into full-on sleet, and we halted for good at, I believe, Banbury.

The railway people apologized profusely but said we didn’t have a choice for safety reasons. So here I was, stuck at an unfamiliar station in an unfamiliar country in freezing cold rain with about half a dozen drunk metalheads from Birmingham whose train had been stopped going in the other direction. However, the railway actually came through and scheduled cabs to take us to our destinations — but I got paired with the drunk Brummeys, so I ended up going quite a bit in the wrong direction before spending a very long, awkward ride with just me and the driver, all the way back to London. (Not that I don’t appreciate the ride or anything, since it was damn awesome for the railway to do this for me.) The cab dropped me off at Marylebone, since that was my original return destination, and I had to figure out a bus route back to Hampstead.

But remember I just came from a wedding reception, where I had a lot of wine. And also it’s like 2:00 am and I had a really stressful moment where I was stranded in the West Midlands. And also I still hadn’t figured out the damn London bus system.

So I don’t get home until four in the morning, extremely tired and cranky. The house, when I unlock the doors and step in, is completely silent, of course. Now, to give you an idea of the set-up, directly in front of the door and to the left was the stairway leading up to the room my roommate and I shared, which was just off the landing there, along with our bath and loo. The sitting room was another floor up, and Clarence and Emma’s room was above that. On the ground floor, to the right, were doorways to Clarence and Emma’s in-home offices. Meanwhile, in between the stairs and the office doors, heading to the very back of the house, was another doorway: to the kitchen.

The kitchen, of course, was dark and empty.

Wanting very much to go to bed, I kicked off my shoes on the mat by the door and went to the kitchen to drop the sandwiches (now quite smashed and gross) I’d taken from the reception in the fridge. Then I went back and trudged upstairs, intent on going to goddamn bed.

And someone followed me out of the kitchen.

Recall, the stairs are running parallel to the little hall into the kitchen, I could see over the railing out of the corner of my eye, and for one surreal fatigued moment I was absolutely sure that someone had walked out of the kitchen and was looking up at me.

I froze on the landing, soaked and miserable in my heavy black overcoat, trying to get over the sudden adrenaline spike, and looked down at the empty hallway. I chalked it up to being completely exhausted, shrugged it off, and went to bed.

I didn’t think about what had happened over the next few weeks because I managed to successfully rationalize it. When the next thing happened, at the end of February, the events were so distinct and the former incident so distant in my mind that I didn’t really make a connection between them until after the fact.

My roommate talked in his sleep sometimes, you see. Not unusual, and most of the time it was pretty funny. He’s musically inclined, my roommate, and he actually beat-boxed in his sleep at least twice. But near the end of February, after a weekend trip to Edinburgh with some friends, we both got outrageously sick. I got over it before he did, so he ended up spending a few days extra in a medicated haze, sniveling on his bed and popping cough drops. One night he went to bed earlier than I did, and as I was just about nodding off he began to talk in his sleep.

“Where are you going?” he said from the other side of the room.

Imagine an American dude with a head full of mucus speaking. Now imagine that he’s not just talking, but trying to mimic an English accent, and he’s one of those Americans who literally just cannot do an English accent to save his life, but he’s trying anyway and it’s terrible. That’s how my roommate was speaking.

“Where are you going?” he said. “Wait, wait, no. Please, don’t.”

My reaction goes something like surprised to amused to annoyed, since I’m hoping he’ll shut up soon so I can sleep.

“Don’t go,” my roommate says, practically pleading now. “No, please don’t leave.” Then, suddenly, without warning he sits up in bed and turns to me: “It’s really bright,” he says, in his normal if congested voice. “Don’t you think, Michael,” he asks, “it’s really bright?”

It’s almost like midnight so of course it’s not bright, but I go ahead and agree with him since it’s just sleeptalk. “You should close the curtains,” he says to me.

The window in the room is closer to him, so I don’t know why I should be the one to do anything about it, but again, I agree. “Are you closing the curtains?” he asks.

Yes, I tell him, I’m doing it right now. (There were, by the way, no curtains in the room, only blinds.) “Good,” my roommate says, satisfied. “That’s good. Now we can sleep. They won’t find us now.” He giggled as he lay down, as if this were somehow amusing in and of itself.

We went to sleep. Again, I didn’t connect any of this with the overall arc of events until much later. I’ll explain in the end, and even then I might be wrong. This might have just been crazy flu sleep talk.

Anyway, time passed, I had classes, adventures in a new contry and so on. The housing situation was pretty good, and I didn’t have much to complain about. There was one thing that sometimes got on my nerves, though: I’m a light sleeper naturally, and sometimes my host-mom Emma would stay up late watching TV in the sitting room just one floor up.

Normally this wasn’t a problem, but sometimes the sound would get kind of inexplicably intense and it would sound like the TV was right outside of our room, just outside the door. I’d roll over in bed and wake up for a second because like late-night reruns of The Simpsons were suddenly audible, and on at least one occasion I heard Irish folk music, clear as day. More than once, however, I heard the sound of children. You know how kids sound when they’re trying not to be heard — whispering to each other, laughing, walking very low to the ground, almost crawling. I could hear them, almost as if they were right out there on the landing.

This happened often enough that I wondered what sort of crazy late night TV show in the UK would always sound like children playing, but unless there’s something I missed while there, I don’t actually think such a program exists.

I started an internship at a certain arts organization in Covent Garden at the beginning of March. My classload was halved so I had time to work three days out of five, and I had to dress business casual and carry around paperwork, and I was part of the morning commute into work and the evening commute back home, and it was all quite exhilarating and professional. I was miserable, of course, because it was work and work sucks, but really I had a very chill environment. A lot of the time I was just transcribing poems for digital archival, and sometimes if I finished a bit early my supervisor would tell me to head on home.

One day I got out early, unlocked the door, and stepped inside. “So you’re finally home?” Emma called from the kitchen.

Normally she just said hello, so I was understandably a bit confused. “Hello,” I called back. “Did you need me for something?”

Emma didn’t say anything in response.

I walked to the kitchen and found it empty. I checked the offices — also empty. The sitting room, the upper floors, all empty. My roommate wasn’t in, since I was off early. I was alone in the house, and the more I thought about it, the more I thought that the voice I had heard — though undoubtedly a woman’s — hadn’t sounded like Emma at all.

Thinking about this, I remembered the incident upon my return from Stratford when something had seemed to follow me out of the kitchen. I began to wonder if the events were somehow related. I’ve maintained, time and time again, that I am not a superstitious man, but when things happen, or seem to happen in certain ways, I am inclined to entertain possibilities. I decided, at the risk of sounding like a doofus, to ask my roommate if he’d noticed anything strange.

I did this by asking him what he thought about the kitchen, which he interpreted as me asking what I thought about the facilities Clarence and Emma provided us. I clarified: no, I mean, what did he think about the kitchen in a more abstract way, like, was he comfortable there?

Well actually, my roommate admitted with some hesitation, he was kind of weirded out by the closet.

Honestly, I had never paid attention to the closet in the kitchen before. It was just beyond the stove, a little alcove beneath the stairs, all Harry Potter-style. What was it about the closet, I asked him.

He asked me if I was serious and said he couldn’t believe that Clarence hadn’t shown me.

Shown me what?

So my roommate showed me.

And now I’ll show you.

This is the closet in the kitchen. The doorway to the left leads to the little entry hallway, the stairs up to our room, and so on.

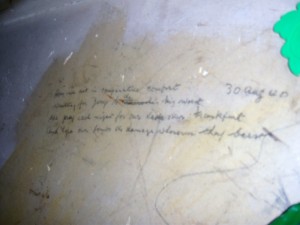

Graffiti inside the closet, written perhaps in charcoal. The date to the upper right says “30 Aug 40.” The poem, though cramped, runs thus:

Here we sit in comparative comfort

Waiting for Jerry to do his worst

We pray each night for our lads over Frankfurt

And hope our bombs do damage wherever they burst

“Heil Hitler — the rotter.”

The Führer has been thoroughly humiliated — he has a black eye, bandages, and “R.A.F.” tattooed on his forehead. Winston Churchill looks smugly on, puffing his cigar.

Obviously this is a neat little bit of history, something Clarence and Emma had discovered after purchasing the house and immediately lacquered over to preserve it. They’d shown it to my roommate one day while I was out.

Notably, the graffiti is dated a little over a week before the London Blitz actually began — so I guess it was made during the drills in the lead-up, which would have happened probably every night and lasted for a while. You’d need to keep yourself entertained if you spent the whole time in a cramped closet underneath the stairs. So maybe you’d bring along a charcoal pencil.

The handwriting on the poem seems to indicate an adult woman — the second bit of writing, over the cartoons, seems to be a different hand, though not as feminine. It might belong to a younger man, perhaps a teenager, a little angry that he couldn’t be the one to give Hitler those bruises.

I don’t think there was an adult man in this closet when these drawings were made — and this makes sense, to a degree, at a time when most able men were enlisting. However, something that I think is particularly notable are the bits that aren’t poems or doodles, the random lines and scribbles in between the drawings. The kinds of things children make.

There are no further doodles in the closet. When the Blitz properly began a week after the poem was written and the danger the Luftwaffe presented was fully understood, the children, both young and teenaged, were probably evacuated for safety, staying in rural abbeys or the country homes of the gentry. The adult woman — their mother, I imagine — went with them.

But later on, I remembered that one whole side of the townhouse had been wrecked by German bombs. I remembered that all the neighboring houses were long gone, and the ugly building of flats next door had, like sediment, settled into the cracks of history.

Clarence did not mention to me that their house was haunted until a few weeks before I left. I’d seen two ghost-centered plays (The Woman in Black, an old standard, and Ghost Stories, a new play that I saw in Hammersmith, but it’s recently got a West End transfer). Clarence, being a bit of a theatre aficionado, wanted to know how I’d like them. At some point during the conversation he said to me “You know, we had our own ghost here when we moved in.”

I certainly had not expected him to say this — he and Emma were, I thought, fervent atheists and were constantly railing about the government paying for the Pope to visit — but I was also further confused by his remark — had a ghost. I asked him what sort of ghost this was.

“A man,” he said. “A man in a black overcoat. He would stand on the stairs, actually, just on the landing outside of your room.” Clarence had seen this man several times, and so had their daughters, when they were young girls. Emma, for her part, had never glimpsed it, but Clarence swore he’d always caught this man just out of the corner of his eye, or just as he walked into the house. A tall, lonesome figure in a black coat, standing on the stairs and, as Clarence described it, seeming incredibly sad.

I asked what had happened with this ghost. Nothing much, Clarence told me. He (the man) had just stood there. Personally Clarence had never had a problem with him, but it bothered the girls terribly — they didn’t like how sad he seemed.

So, again, what happened?

“Well,” Clarence said rather matter-of-factly, “we had him exorcised.”

Again, Clarence had told me time and again he was an atheist, but in retrospect I knew he was also really into that James Lovelock Gaia thing, so maybe this shouldn’t have surprised me so much.

The exorcism had apparently broken down like this: Clarence knew some people who knew some people. A psychic investigator had been hired and confirmed the presence of an entity on the stairs, a man in black whose primary aura seemed to be one of sadness. As Clarence explained it, the man in black felt like he had left something behind. The investigator had then walked up the stairs and began to speak to the thin air. “It’s okay,” he said. “You can leave. It’s not here anymore, whatever you left. There’s nothing here for you now.” There were, apparently, a few minutes of stuff like that.

And I guess, somehow, it worked.

“We never saw him again,” Clarence said.

And I never saw him at all.

I never told anyone expressly about what I thought I had seen, and especially the things I thought I’d heard. The things I sometimes still heard, or thought I heard, when I woke up in the middle of the night; the sensation I always had when, alone in the kitchen, I felt as if someone were standing very, very close to me.

It wasn’t until the end of my stay in London that I started to put things together.

I thought about the man in black, and his loss. The things Clarence told me the investigator had said. There was nothing here anymore.

I thought of all the able men, all the men of age, enlisting to fight the encroaching might of Germany, leaving behind their children and families, not knowing that soon the Axis would be at their very door.

Surely some of the soldiers lived, but returned home to find their houses and their neighborhoods decimated, family members missing. How sad they must have been, how alone.

And I thought of the families left alone, hiding in closets, waiting for the inevitable, passing their time in the dark. England had, after all, been under a blackout to make the cities harder to spot from the air. I remembered what my roommate had said in his sleep, about it being too bright, that we should close the curtains. I had assumed he meant bright outside, but what if he meant the opposite? And I remembered his pitiful pleas for someone to come back — not to leave.

It occurred to me, in time, what I had looked like on that January night, seemingly forever ago, when I’d stumbled into the house at four in the morning, rooted through the kitchen, and started up to my room.

I had stood there on the stairs, and I was sad and scared but I was also glad to be someplace that felt like home. And someone or something, seeing me in my black overcoat I got on sale at Kohl’s three years ago, had mistaken me for someone else, and come out to welcome me back.